A track record of results

Gemstones: Revealing Origin, Changing Lives

I have been leading innovation in colored gem supply chains since 2017. My previous and ongoing gemstone work has brought me to Ethiopia, Madagascar, and Malawi. Read more here.

Critical Minerals: Protecting Children

From DRC to Zambia, my work has helped to bring critical services and funds to withdraw child miners from dangerous situations. This case study focuses on Zambia.

investing in the women miners of east africa

Developing breakthrough sustainability programs

In 2017, the jewelry sector was a very different place. While there were a few options to buy responsible gold, the colored gemstone sector was frequently referred to as ‘the wild west.’ This was because artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) dominates gemstone production and they are a highly mobile, mostly informal, population. In 2017, establishing origin in ASM supply chain was widely said to be ’impossible.‘

Furthermore, traditional gemstone dealers tend to be secretive about everything. (Sometimes this is for good reasons, such as personal security). Unfortunately, however, sometimes this secrecy is to prevent change to one’s business model, which keeps miners dependent on an outdated system of trade. This trade may be beneficial for miners in some locations, where cash is needed, roads are poor, and where they may receive a ‘fair‘ price. However, in many more situations, it is a cruel irony that gemstone miners pull luxury materials from the Earth and are working while hungry because of the low prices they receive.

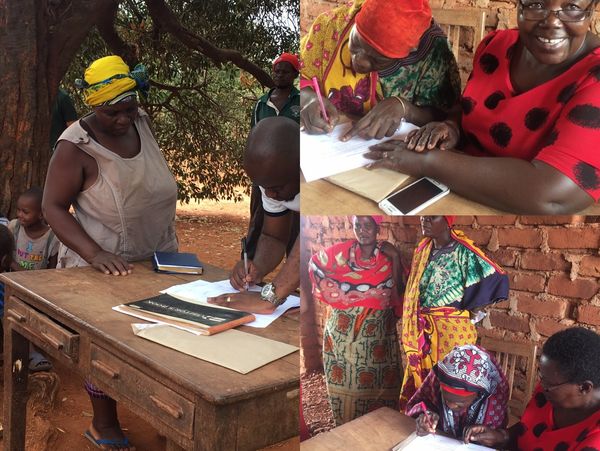

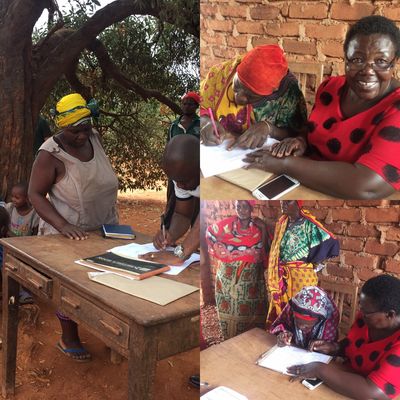

I had met the Tanzanian Women Miners’ Association (TAWOMA) during my 11-year tenure at Pact, a global development NGO. There, I had been developing an educational collaboration with the Gemological Institute of America (GIA). The gemology collaboration aimed to teach gemstone value-factors to artisanal miners, help miners understand how to pre-sort their gems by value, better understand the various gemstone value chains (e.g. fine gems, specimen markets, bead and carving quality, etc.) so that ultimately miners would be able to use gemstone education to change their own lives. It worked. The initial pilot class of women miners improved their incomes between 3 to 5 times. GIA trainers would return to the initial sites again and again over the years to marvel at the visible changes and stories of impact within the rural community.

“The miners can now sort, they know how to wash their gems, and they can add value into the material … They are really now getting more money than when they didn’t have this project. It has added a lot of value into their life using the book and the tray,” said Salma Kundi Ernest of TAWOMA, the Secretary General of TAWOMA. She was referring to the free GIA Colored Gemstone Guidebook and accompanying gemological tray, where miners are taught to pre-sort their rough. Beforehand, the women miners had been selling their high and low value gems together out of ignorance. In colored gems: knowledge is power.

At the end of the 2017 pilot program (which would eventually expand), the women gem miners in Tanga requested more market opportunities to sell their gemstones. They said that their rural location limited their sales opportunities and their own poverty limited their mobility to travel. At the same time, when I was giving presentations to the jewelry sector about this program, the most common question that I would receive from the audience was: How do we buy gems from these women miners? The Moyo Gems program was born shortly thereafter.

Moyo Gems means ‘heart’ in Kiswahili and ‘life’ in additional languages in the region. In 2018, I identified industry partners ANZA Gems and Nineteen48 and we traveled to Tanzania to meet the miners and co-design a possible program. The miners never expected our group to come back… but we did. Again and again. From 2019, when the program launched, it has grown from 91 miners to more than 1,000 today. It is now 50-50 women and men in order to not isolate women (a security measure) and to ensure widespread community support for the program. It remains the highest-gender diversity of any program in jewelry.

Miners in the Moyo Gems footprint of Kenya and Tanzania tell me that they love it because it was designed for and by them. The miners are pre-vetted before they are invited to be a part of “Market Day as Moyo Gems miners. When they make a successful sale, they make 95% of the export price of the gems.

Host governments love it because all taxes are paid on behalf of the miners, formalization is required (and is supported by the national women’s mining association partners: AWEIK and TAWOMA), and it has channeled investments into the villages and into value addition. Young people — aged 18 to 30 — are now adding value to the gemstones in both Kenya and Tanzania via the GemFund and TAWOMA Youth organizations, which are now a part of the Moyo Gems value chain that maximizes local value, national talent, supply chain transparency, and tax revenue.

I am no longer involved with Moyo Gems, but I continue to be proud of its impact. It shifted the conversation in jewelry. Engaging rural communities is no longer considered ’impossible.’ … Who is behind your gemstone?

Read more here:

“The Hidden Journey of the Women Gemstone Miners of East Africa,” in Gems & Jewellery Magazine. Published by the Gemmology Association of Great Britain. Summer 2025. Print and Online Edition. (click link or scroll below for PDF)

Interview with Cristina Villegas on the topic of Colored Gems & Gender, with the Watch & Jewellery Initiative 2030. Online: https://www.wjinitiative2030.org/sharing-perspectives-4/ (March 2023)

Baseline report of gemstone mining dynamics in Kenya‘s Taita Taveta County. Funded by UK Aid. Available online. Study undertaken in 2017 and published in 2018. The Moyo Gems program was launched in 2022 in the same area as the UK Aid study.

Selected program press

Le Point (France) — March 2025 - “Saphirs Ethiques”

https://www.lepoint.fr/montres/saphirs-ethiques-25-03-2025-2585604_2648.php#11

Volkskrant Magazine (Netherlands, a major daily newspaper) — March 2025 “Steengoed” (Good Stones). Print edition only.

Diamonds Do Good— “GIA Gem Guide Delivers Education, Social Return to Artisanal Miners.”

https://diamondsdogood.com/gia-gem-guide-delivers-education-social-return-artisanal-miners/

Robb Report - February 2022- "7 Ultra-Rare Precious Stones We Saw at the Tucson Gem Shows"

https://robbreport.com/style/jewelry/tucson-gem-show-highlights-1234662472/

France Channel 1 - December 2021 - "Les coulisses de la place Vendôme / Grands Reportages"

https://www.tf1.fr/tf1/grands-reportages

The Financial Times (Denmark) - December 2021 - "køb diamanter med tjek på etikken" / "Buying verified ethical diamonds" (print only)

The Financial Times (UK) - How to Spend It - November 2021 - "The Good Gems Guide"

https://www.ft.com/content/9ec1b86d-b9b8-46c6-9e1b-57b13b0aef93

National Jeweler - November 2021 - "Moyo Gems Is Expanding Into Kenya" https://www.nationaljeweler.com/articles/10369-moyo-gems-is-expanding-into-kenya

Rapaport Jewelry Connoisseur - September 2021 - "Women's Work"

https://jewelryconnoisseur.net/womens-work-moyo-gems/

National Jeweler - March 2021 - "Brilliant Earth Launches Moyo Gems Collection " https://www.nationaljeweler.com/articles/8641-brilliant-earth-launches-moyo-gems-collection

British Vogue - September 2020 - " Good News: In 2020, Sustainable Jewellery Is Finally Top Of The Agenda"

https://www.vogue.co.uk/fashion/article/sustainable-jewellery-technology

Scottish Sunday Post - November 2019 -- "Miner miracle: Scots jeweller joins global fight to end unethical trade in gems from Africa" https://www.sundaypost.com/fp/moyo-gemstones/

National Jeweler - October 2019 -" You Can Now Buy Stones from Moyo Gems"

https://www.nationaljeweler.com/blog/8227-you-can-now-buy-stones-from-moyo-gems

National Jeweler - April 2019 - "Sustainability Stories: Mine to Market with Moyo Gemstones" https://www.nationaljeweler.com/blog/7668-sustainability-stories-mine-to-market-with-moyo-gemstones

Forbes -- April 2019 -- " Moyo Gemstone Collaboration A Model For Responsible Jewelry Initiatives "

https://www.forbes.com/sites/andreahill/2019/04/26/moyo-gemstone-responsible-jewelry-initiative/

Social Media

The Moyo Gems program is on Instagram: @MoyoGems

Also follow the Moyo Gems partners!!

To view or purchase gems:

- ANZA Gems @anzagems (Buy the gems directly!)

- Maison Piat @moyobypiat (for purchasing gems directly)

- Nineteen48 Gemhouse @nineteen48 (for purchasing gems directly)

To learn about the work and hear from the amazing partner organizations:

- Association of Women in Energy & Extractive Industries in Kenya (AWEIK): Instagram is @aweik_ke

- GemFund: Instagram handle is @gemfundorg

- Tanzanian Women Miners Association (TAWOMA): Instagram handle is @_tawoma

- TAWOMA Youth Gem Workshop: Instagram handle is @tawoma_youth22

Critical Minerals: Protecting ChildreN

Teaming up with companies, communities, and governments

Context: Zambia is at the center of a new mining boom. Seasoned miners and new entrants are focused on the new gold discoveries in North-West Province and beyond, and reprocessing so-called ‘critical minerals’ tailings from the country’s historic mining regions of Copperbelt and Central Province.

‘Critical minerals’ is a new term for materials with a deep history in the country. Zambia’s once prosperous copper and cobalt mining economies collapsed many decades ago with the breakup of ZCCM, the state-mining company, and the exit of Anglo-American, the large multi-national mining company.

In the aftermath, those families who remained had dramatically fewer income sources. Following a series of economic shocks, the most vulnerable families were barely getting by. Zambia’s child labor problem began to swell and children were in increasingly precarious situations. The most common kind of child labor was children working alongside their parents, and the second most common were pre-teens and teenagers mining slag heaps and whom were under the direct control of ‘jerabo’ gangsters that had filled a governance vacuum in parts of the country.

Mining is considered a ‘worst form’ of child labor by the International Labor Organization due to the severe physical and psychological risks for girls and boys who are involved in this work. While there are critics that romanticize child labor and downplay its risks, it’s critically important to note that mining remains one of the most dangerous professions in the world. It is no place for children. Girls often suffer additional traumas that are rarely acknowledged.

My role: In 2020, I led a partnership with the London Metal Exchange (LME) via my previous role at Pact. My colleague Dylan McFarlane had engaged the LME after witnessing children on mine sites across Zambia. LME acted with leadership and conviction, and funded two projects to work in Zambia and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Dylan was set to lead the Zambia work, and he died unexpectedly just before work began. Honoring his legacy, I took over, shaped, and launched the project. It would ultimately have the following features:

1. It was data-driven. I wrote the scope of work and oversaw the recruitment of the top child rights researcher in the country to study the area intensely with a data-collection team of his choosing. I wanted to understand the profiles of the working children, why they were there, the ‘push and pull factors’, lessons learned from other programs, local beliefs about child work, and local governance factors. The research was so detailed that the Government of Zambia adopted it as officially recognized data early in the project. It helped give them a blue-print too.

2. It was child and family-focused. When I hire staff, I typically hire equally for soft and hard skills. In this role, I knew I needed a child rights professional and not necessarily a ‘mining specialist’. It’s hard to teach true passion and I needed someone with deep expertise in protocols around vulnerable children. So I chose to hire for that and ’teach them everything they needed to know about mining‘ after they were hired. I found my project leader — Fabian Miselo — who already knew quite a bit about mining because he was from the Copperbelt and had seen the arc of development from mining boom to bust. He was not an ‘administrator’; he was (is) a leader. And then he hired his team.

3. The project focused on strengthening the Government of Zambia to regain control of the issue, such as improving their own understanding and staff protocols. This included:

- Establishing Standard Operating Procedures when their mining officers encounter vulnerable children on mining sites;

- Improving the frequency and quality of mine site inspections;

- Increasing enforcement against those who are manipulating or controlling children;

- Establishing better data systems, and more.

4. The project also focused on choices and agency. For the families that were sending their children to the mines, the project engaged the parents (or other caretakers) to focus on household economics and diversification beyond mining. As is common, a breakthrough occured when the project focused on the mothers of the vulnerable children. Reducing mothers’ economic and social vulnerability has well-established demographic dividends. The project established 18 women’s groups, reaching approximately 500 vulnerable women and reaching nearly four thousand children in its target communities in six districts.

For some of the older children who could not be reintegrated into school, the project was able to offer age-appropriate, safe, and marketable vocational training for girls and boys in subjects such as carpentry, auto-mechanics, sewing, hospitality, electrical, and other fields.

Ultimately, I transitioned the project to an internal expert on the global responsible mining team that I was directing. She built links across portfolios for the Zambia team to benefit from colleagues in DRC, Colombia, Madagascar, and beyond. For me, I knew Dylan would be proud of the work he catalyzed and that I was able to improve and take forward.

Read more:

- 2023, London Metal Exchange: “Women In Mining Communities”

- 2022, London Metal Exchange: Program Update

- 2021, London Metal Exchange: “LME Partners with Charities…”

Copyright © 2025 Nature's Wealth LLC. - All Rights Reserved.